A Different Kind of Elephant

Forest elephants are the least well known of the three species of elephants. Found in the rainforests of the Congo Basin of Central Africa and in small, isolated populations in West Africa, their habitat, diet, size, and even DNA make them distinct from Asian and African savanna elephants. They are the largest rain forest-dwelling mammal, adapted to survive in the dense vegetation.

The last living elephants with a chance at preserving their original lifestyle

Forest elephant populations are in severe decline due to habitat loss and poaching for ivory. If we can stop, or even reverse, this decline, forest elephants actually have the best chance of any elephant species to persist with the full range of behaviors and landscape movements that evolved for survival in their rainforest home. This is because there still are huge expanses of relatively unexploited forest in Central Africa (the second largest tropical forest landscape on earth), and the human population density is relatively sparse and urban. Elephants can move across quite large distances and in East Africa and Asia they are increasingly fenced into protected areas, causing a suite of management problems. Keeping forest elephants roaming freely through Gabon and Congo and Cameroon is our goal.

Evolution

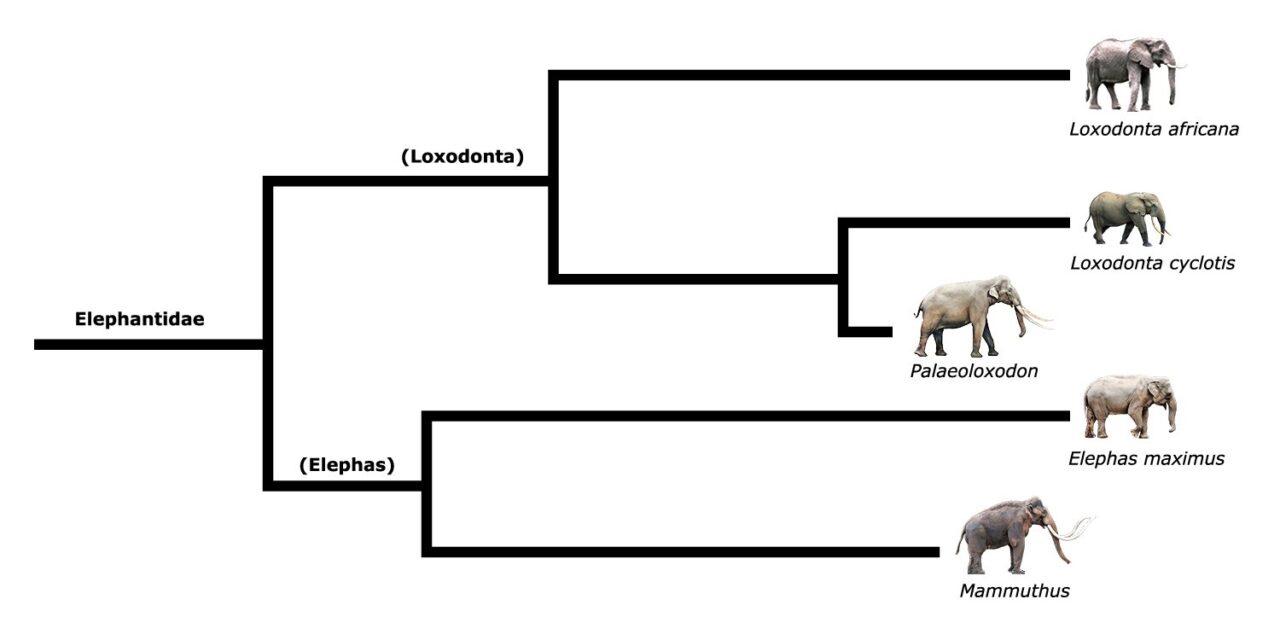

Only in 2013 had sufficient evidence accumulated to consider the forest elephant its own distinct species (Loxodonta cyclotis). Before this, the savannah or bush elephant and the forest elephant were considered subspecies of the inclusive taxon Loxodonta africana. Recent analysis of DNA from fossils reveals that forest elephants are more closely related to the now-extinct straight-tusked elephant (Paleoloxodon antiquus) of European forests than to any other living elephant (1, 2).

Despite their clear genetic and morphological differences, the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) has not yet acknowledged cyclotis as a species. It has now been fifteen years since the IUCN released a statement citing the “uncertain” taxonomy of elephants, and calling for further evidence before determining the relationships among existing elephant populations (3). This delay, which is mostly due to politics, has far-reaching consequences for elephant conservation (read more below).

The relationships among the extant (living) elephants shown above would have been controversial several years ago. It takes the scientific community a long time to debate and accept changes in the species designation of an organism, particularly mammals. Changes in bird taxonomy are often decided more efficiently because a specific organization has been vested with the authority to do so. In the mammal world there is no parallel structure.

For example, an analysis of elephant skulls collected across Africa proposed that forest elephants “deserve to be ranked as full species.” This study, done by Peter Grubb and colleagues (4), concluded that “living bush and forest African elephants are evolutionarily and ecologically distinct forms.” What the discussion lacked at the time was genetic evidence. With the appearance of elephant research that included genetic sequences, we have now learned “that little or no nuclear gene flow occurs between forest elephant and savanna elephant populations” (5). In fact, forest and savannah elephants may be as genetically distinct as mammoths (Mammuthus) and Asian elephants (Elephas maximus), which are considered to be different genera (6). More on elephant evolution below.

A Conservation Dilemma

These taxonomic issues are more than an evolutionary debate within the scientific community. Classification of the species is important for the conservation of forest elephants. It might have been easier to ignore the decline of forest elephants if they were seen as populations within the African elephant species (in fact, the relatively poor data on forest elephant populations before 2013 resulted in conservation decisions by the IUCN and CITES that essentially ignored forest elephants). However, once it is acknowledged that the forest elephant is a unique species, the importance of their conservation rises greatly. The threat of biodiversity loss is increased even further because forest elephants have the highest within-species genetic diversity of all elephantid taxa (4). Hopefully, as the new taxonomic order enters mainstream scientific thinking as well as the imaginations of the public and of policymakers, it will facilitate the effort to study and conserve forest elephants.

What We Know About Families

Families are at the core of all elephant societies, but the size and function of this most basic unit for forest elephants is only just beginning to come to light. Concealed by the forest canopy, they seem to search for food and resources in small groups, just a mom and her calves, but a more complex family structure emerges in forest clearings. How different are these elephants of the forest from the other, better known, elephant species?

Elephants have the longest gestation period of all mammals – 22 months, and forest elephants produce a calf only once every 5 to 6 years. This lengthy time interval allows the mother to devote the attention that the calf needs in order to teach it all the complex tasks of being an elephant, such as how to use their trunk to eat, drink and wash, and what to eat.

The average forest elephant core family size consists of 2.8 individuals, comprised of a mother and her dependent offspring, but extended families can include as many as seven elephants. Young males form part of these groups until they disperse at around the age of 14.

Families usually visit clearings 2-3 times a year, for two or three days in a row (although some come more often). They often make these visits the same week and month, year after year.

Often it seems that subgroups of an extended family arrive at a clearing close together in time. But do these subgroups travel together in the forest or do they “share a plan” for when to meet at the bai? We still don’t know.

By the Bai – Glimpses of a Social System

The mystery of forest elephant society emerges through observations at forest clearings or “bais” (a local term for certain types of clearings). Here we see the extent of relationships maintained among a network of individuals much larger than the core family group.

Forest clearings like Dzanga provide the rare opportunity to actually observe forest elephants and their interactions with one another. Much of what we know about the social structure of forest elephants comes from observations of interactions at the Dzanga forest clearing by our colleague Andrea Turkalo. Her 27-year long observational study at Dzanga bai, and her familiarity with thousands of individuals, makes the site unique among the already limited few that have received long-term observations.

Elephant Society

Elephants have one of the most complex societies in the animal kingdom! This complexity is the result of their ability to recognize and track other elephants over long periods of time despite changes in age, status, and condition. Over their 65-year lifetimes, elephants develop multiple, many-layered social relationships that even account for individual personalities.

Generally, forest elephants appear similar to the better known savanna species in terms of female group interactions and male behaviors, but it is important to keep in mind the limits of our current knowledge.

Families come together at forest clearings where they re-establish bonds, meet new infants, and likely engage in many social interactions we have not yet identified. Males and females looking for mates might also be attracted to clearings. Males leave the family in early adolescence, after which their social activities consist mainly of competing for rank in male dominance hierarchies. Savanna elephant males spend considerable time roving among family groups in search of females. It is possible this also occurs in the forest elephant, but male forest elephants might instead depend on finding females at forest clearings.

Adult bulls have no involvement in the care of young. Females, on the other hand, spend their lives immersed in a social network which encompasses many families and several levels of competitive and collaborative relationships. Communal care of young is a conspicuous feature of the female society and forest clearings have been an excellent place to observe this ‘alloparenting’ in action.

Babies

One of the joys of studying forest elephants in the field is being able to watch the infants. Our researchers have been privy to many magical moments in the field, both endearing and amusing.

Elephants have the longest gestation period of all mammals – 22 months, and forest elephants produce a calf only once every 5 to 6 years. This lengthy time interval allows the mother to devote the attention that the calf needs in order to teach it all the complex tasks of being an elephant, such as how to use their trunk to eat, drink and wash, and what to eat.

Soon after birth, elephant babies can stand up and move around, which allows the mother to roam around to forage. The calf suckles using its mouth (its trunk is held over its head). The tusks erupt at about 16 months. Calves are not weaned until the next younger sibling is born (when they are about 5 years old). Even without a new sibling, by five years of age the tusks are about 14 cm (5.5″) long, and begin to get in the way of sucking.

Ecology

Forest elephants are now accepted as a unique species of elephant (Loxodonta cyclotis), distinct from their better-known cousin, the African savannah (or bush) elephant (L. africana). This designation reinforces what scientists have always recognized: that forest and savannah elephants have very different ecologies.

Elephants are the largest of all terrestrial mammals and the three extant species (the two African species plus the Asian elephant, Elephas maximus) share many life-history characteristics. They have a natural life span of 60-70 years and mature slowly, reaching puberty in their early teens. A recently published study revealed that forest elephants have a considerably slower reproductive rate than the other species of elephant. Although females are fertile at about age 13 (as are savannah elephants), the average forest elephant female does not have her first baby until 23 years of age—ten years older than for savannah elephants (1). Forest elephants also separate sequential births by more than five years, while for savannah elephants this is closer to four years. Together with the poaching pressure these populations are experiencing, this very low reproductive rate makes the future of forest elephants more precarious than previously thought.

The rainforests of Central Africa (second only to the Amazon in extent) have profoundly shaped both the diet and the social system of forest elephants. Elephants eat large quantities of fruit, leaves and the bark of trees as they wander in small family units, usually comprised of a mother and one or two of her dependent offspring. Although suitable browse is probably found in most parts of the forest (elephants are generalists, so many species of plant are eaten), fruit trees and mineral deposits are both spatially clumped. This has probably selected for the smaller group sizes that we see in forest elephants compared to their savannah cousins. Forest elephant movements are also influenced by forest clearings (called “bais” by the local Bayaka) which provide mineral supplements to their diet and facilitate social interactions. Individuals have been known to travel over a hundred kilometers to reach these bais, the only known places where large numbers of forest elephants gather to meet, greet friends and family, play, and mate.

More than half of a forest elephant’s diet consists of various tree parts, such as leaves and bark, and they are notorious fruit-lovers. In one study, fruit remains were found in about 83% of dung piles examined by the researchers! Elephants have even developed well-used paths that connect forest clearings and favored fruiting trees. By dispersing fruit seeds after digestion, forest elephants have created corridors abundant with their favorite fruits. Their role as rain forest engineers further underscores the critical importance of forest elephants to their habitat.